4th February 2023

Director: Kim Jong-kwan

A tale of loss and loneliness, memories and dreams and the dichotomy between life and art. Various unrelated people relate their personal tragedies to a seemingly dispassionate protagonist until we piece together his own story, and the film feeds back on itself; we end where we entered but now enlightened. A trailer may be viewed on YouTube:

‘Shades of a Heart’ is a rather slow-paced movie, somewhat in the style of fellow Korean director Hong Sang-soo. The supporting characters, detached from each other, give the film a vague European, existential air, while the cinematography and use of colour remind me of Hong Kong’s Wong Kai-wai, who also explores similar themes.

What follows is my interpretation of the film and as such, I shall be writing about the film beginning to end.

Watching the first time, I did find the film a little slow in places probably because we learn so little about the main character, Chang-seok. However, by the end I knew I had to rewatch the movie. My second viewing was now informed by my first. Yes, it was well worth the time.

The film is divided into six unequal chapters, four devoted to the supporting cast, one as a voice-over, and only at the end in chapter six do we learn about Chang-seok. Most chapters take place in one location, giving the film a theatrical quality.

Imagine a black stage. We hear a male voice saying that he sees himself, from behind, walking next to an old woman. His wife ? Mother ?

Cut to Chapter One, Mi Yeong

A café that is located in an underpass or subway. A young lady is sleeping, resting against the glass, then wakes. Our first view of Chang-seok is a close-up of the book he is reading. Immediately, we have themes of dreaming and literature. Suddenly the camera angle changes, and their positions are reversed. Mi Yeong is now camera right, Chang-seok on the left. We also view them from outside the café, giving a disconcerting, distancing effect.

After apologising for sleeping, Mi Yeong (played by K-Pop star IU) asks the man why he sits with her when there are so many empty chairs. He is here to meet her; they have been set up, a blind date which gets off to a bad start when she sees the book. Mi Yeong doesn’t trust fiction, as it is made up. Chang-seok is a writer. He makes up a story for her, about a tramp who revisits a hotel where he used to rent a whole suite. Only the old bellhop remembers him. A throwaway story, but another chance to introduce themes of loss and memory.

Mi Yeong appears bored and about to sleep. Before doing so, she tells about her boyfriend, how they met in this very café on a blind date. She then warns Chang-seok not to smoke, as his father had done.

Short focus lens, representing reality and unreliable memory.

“So now you recognise me ?” he asks.

The camera cuts back to the former reverse angle, only now, Mi Yeong has been replaced by an old woman. She has been reliving her meeting with Chang-seok’s father, who has now passed away. We see her wedding ring. Mi Yeong is not some flighty sassy girl, but a grieving, possibly ill, elderly lady.

Look around the café; solitary people sit, reading books or newspapers. One man even plays a board game alone. Loneliness, literature and loss.

We cut to an street scene and get a little of Chang-seok’s backstory. He has returned to Korea after seven years, and has noticed how people have aged. His mother, we learn, will live in a nursing home. Yet, this voice-over doesn’t seem to be addressed to us, the audience, or to a friend. Is Chang-seok making notes for a new novel ?

Yoo Jin is the next character we meet. Spring, we learn, is late this year, and the colours are still deep burgundy and brown as Chang-seok waits for this young lady who works for his publisher. We learn that she worked for him as editor, so they have a professional history. Yoo Jin feels that his last novel was too personal to be fiction, even though the main character dies, which could be a reference to Chang-seok’s emotional life. Something has been lost, but we, at this stage, still have few clues, only that he feels he has no more stories to tell.

Yoo Jin is dismissive of her CEO’s work, and is referred to as ‘harsh,’ and ‘cold.’ However, when she sees a dying bird, she appears troubled and sympathetic. Meanwhile, we see a middle-aged lady talking to herself, muttering about the wind, and asking to hold hands.

A short time later, as they are smoking (Chang-seok has ignored his mother’s warning), we hear Yoo Jin tell her story, about having an Indonesian boyfriend. She got pregnant and had an abortion.

Chang-seok doesn’t immediately react and when he does, it is with a non sequitur, an anecdote about Buzz Aldrin’s book (more literature) ‘Return to Earth,’ meaning that it is harder to return than to leave. Clearly he is speaking about himself.

Yoo Jin fails to see how this connects with her story.

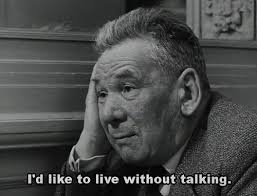

We cut to night scenes, Chang-seok eats in a restaurant, while some women are using sign language in the background. Communication, the need to connect. We see a bar, a close up of a ship in the window. Chang-seok decides not to have a drink. Instead he goes to a phone box, but it has been vandalised. No communication is possible.

Part Four is where we meet Sung Ha, a middle-aged man and former acquaintance. Chang-seok is working on his laptop in another café, and the two meet by chance. Sung Ha seems very upbeat, a little too much, as if it were forced. As Yoo Jin masked her pain by a cold exterior, Sung Ha is the reverse. We see he carries cyanide with him, which he will take when he wife dies.

Sung Ha’s wife has been in a coma and, desperate for any remedy, he sees a Buddhist monk and follows his instructions. Incredibly, the wife seems to have come out of the coma and has opened her eyes.

Then Sung Ha excuses himself as he has a phone call. In that time, Chang-seok takes the cyanide bottle. Sung Ha returns and says he must go to the hospital. His wife has just died.

Ju Eun is the lead in part five. She is working a quiet bar, has short black hair, wears black and has tattoos. Additionally, one eye seems lighter. She exudes an air of coolness, aloofness and indifference. Tonight is, she informs Chang-seok, her last night, so he can stay as long as he likes.

Chang-seok is writing in a notebook, and tells Ju Eun that he is waiting for someone (rather than admit to being alone), but his story doesn’t convince her at all.

Ju Eun likes that he uses pen and paper in this modern age, saying that she uses a voice memo app to record ideas, then transcribes them later. She writes poetry based on her customer’s stories. If the stories are boring, she invents a reason why they are boring.

Without waiting for the question, Ju Eun opens up, explaining that she was in a serious accident, where she lost her eye, was scared on her chest and has lost most of her memory. She offers free drinks to customers who ‘sell’ her a memory which she can record, a form of a Faustian pact.

Chang-seok’s memory story is, perhaps predictably, disappointing and uninspired, yet it pleases Ju Eun. They drink together. Ju Eun’s favourite glass is shown to be chipped, imperfect. She kids him again about waiting for a friend; she has heard all the stories. Chang-seok doesn’t ask her about her future plans

The final part is where we learn about Chang-seok. At home, on his desk, sit the cyanide. He leaves the apartment and goes to a phone box, calling his wife in England. The background music is unobtrusive but ominous.

During the conversation, the wife, who is also Korean, says she misses him and agrees to get back together.

“Soo-yeon misses her Daddy.” This stops Chang-seok, and he tells his wife that their daughter is dead. The wife dismisses this, saying that their child is sleeping next to her. However, the unemotional voice leads us to believe that she hasn’t accepted the death and still thinks the child is alive.

Chang-seok knows that both his daughter and, at least for now, his wife are gone. This can explain why he appeared so indifferent to Yoo Jin’s confession. At home, he prepares the cyanide.

We cut to the blue light of dawn, a new day, new hope. Chang-seok walks past the bar, the toy boat still prominently displayed in the window. He looks up. In the distance, an old man is helping an old lady to walk up a street. Is this Chang-seok in the future ? Does he find happiness with a new wife, or does he reconnect with his present one ?

The picture turns black and white. Suddenly the woman from the Yoo Jin sequence appears, but now she has a small boy with her. The boy is carrying the toy boat, from the bar, and the mother tells him to hold her hand, to stop him losing her.

We see Chang-seok writing. He has a new idea for a novel. He is writing about the happiness he lacks, literature is creating a life. A made up life is better than no life.

He is with his wife. They still love and care for each other after all these years. A young mother is so happy, her son is her entire life. We hear the lines from the beginning, Chang-seok sees himself from behind, he is both observer and observed.

‘Shades of a Heart’ keeps the audience guessing until the very end when we have to re-evaluate Chang-seok and his life. We know things are not what they seem when Mi Yeong transforms from a young girl to an elderly lady, but we are kept waiting until the end for the emotional release, the tears about the dead daughter, the dying mother and a mentally scarred wife.

Kim Jong-kwan has made a film that demands several viewings to appreciate its beauty, delicacy and pain.