29th July 2021

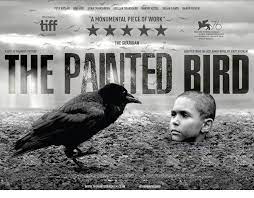

Over twenty years ago I read ‘The Painted Bird’, by the Polish-born author Jerzy Kosinski and, as I was reading it, I knew the images, the emotional impact, would be indelible. Last night, I watched the 2019 film version, and now I hope this blog introduces the work to a new audience.

The book cover succinctly simmarises the tale. The setting is an unspecified area of eastern Europe during World War II. The Nazis are invading, bringing with them their ideology of racial superiority. The Communists are pushing back from the east, while brigands of bandits are attacking hamlets. Destruction, torture and violence. Mankind without the humanity, a return or regression to barbarity. There is – almost – no right or wrong, merely who is the strongest.

The film opens with a boy, Joska, running through some woods, clutching a pet stoat. We can tell he is being chased, although we do not see by whom. Inevitably, he is out-run and out-numbered and Joska is beaten by boys his own age, who take the animal. This is war time, maybe the animal will serve as food for starving villagers … but, no … the animal is gruesomely tortured. This scene encapsulates the theme: brutal violence for the sake of brutal violence. This is the world Joska was born into. No compassion, no empathy, no mercy; kill or be killed.

The Nazis, foreshadowed early in the film by a solitary plane observed by Joska, are just one of many threats. This world, this mid-C20th Europe, is dominated by ignorance, superstition and cruelty, it is the Bible of the Old Testament, animated by Bruegel and Bosch.

Already we have seen boys, children, symbols of innocence and purity, torturing for pleasure. Joska moves from place to place, at the mercy of adults, and cannot comprehend the brutality that is done to him or in his presence. He witnesses a miller, obsessively jealous of his young wife, rip the eyes out of a young apprentice because he dared look at the mistress. While the miller is beating his wife, Joska runs away, looking for the apprentice. The boy tries to help by giving the apprentice some round objects to replace his eyes, then continues his flight realising he has, inadvertently, caused more pain.

Each act of violence serves as an allegory of that world. Blindness, not knowing, not wanting to know. Genocide victims are numbered in hundreds of thousands, in millions. Such figures are beyond our comprehension, so the power of the story comes from seeing evil on an individual level. We become desensitised viewing death en masse. Watching a solitary act of brutality has a far more powerful effect. We feel the victim’s pain and fear, we abhor the evil personified by small groups of people. People who look the same as us.

The title is taken from an episode in which a seemingly pleasant older man collects small birds. He derives pleasure from painting one, then releasing it into the flock. The other birds sense something different and begin attacking. Just one of many incidents of cruelty, but a suitable metaphor, that justifies its prominence.

However, there are some glimpses of hope. A Nazi, expected to kill Joska because he is Jewish, allows him to run away, instead firing two shots into the air. Later a Russian sniper takes to Joska, protecting him. When four Russian soldiers are attacked by locals, the sniper calmly goes to the village and with a long-range rifle, kills four people. He teaches Joska the, “Eye for an eye,” policy.

Read as an allegory, we see all vices and perversions, the depravity that humans can sink to. Yet we also, fleetingly, see hope, warmth, friendship and compassion. We see how insidious intolerance and prejudice can be and what evils it can inspire.

‘The Painted Bird’ is intense in the extreme. For me, it is an unforgettable experience.